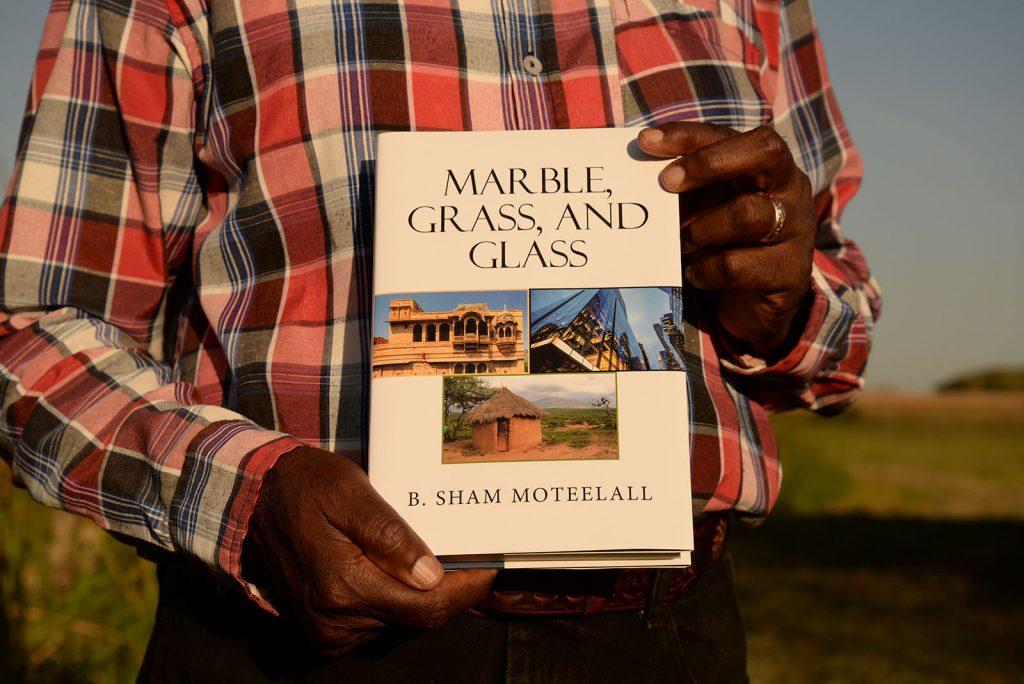

Marble, Grass, and Glass

About the Book

This book delves into the lives of various East Indian indentured servants bound to British sugar plantations in the Caribbean between 1838 and 1917. Some 1.2 million Indians embarked into a contractual agreement to work for a specified period at those establishments during that period. Many were lured with false promises that resulted in an atrocious system that undermined human dignity.

People came under a servitude process that resulted in a system that replaced, redefined, and re-invented slavery. That system determined that not all people were created equally, and the establishments treated them like chattel.

This reflection focuses on the country of Guyana. It progressively talks about ancestors who endured the severity of plantation life and the abuses associated with their daily lives. Those people suffered tremendous hardships. Some died while still bound to the estates leaving orphans behind. Many endured, survived, and prospered. This book is their story.

Preview

Marble, Grass, and Glass, centers on the 1.2 million East Indian indentured servants shipped to various parts of the world to work on British sugar plantations and other entities. Although similar events occurred at their various destinations, the main focus here is on the country of Guyana where some 240,000 Indian subjects were sent.

The indentured process to Guyana started after slavery was abolished in 1834. The first two ships transported and delivered their surviving human cargo there in 1838. The indentured process continued until 1917. Plantation owners were used to slave labor, and their field supervisors called overseers and drivers maintained their ruthless domination over the new arrivals. The term driver refers to those individuals who would “drive” the workers with whips to demonstrate their power to ensure that the quality of work met their high standards and was pleasing to the wealthy English owners.

The indentured Indians, called coolies, left India for various reasons to work at the plantations for a set period of time and return home wealthy. So, they were told. Many were told that they were going to a colony to sift sugar and would be well compensated. The recruitment process turned ugly when it became compulsory that ships must carry a specified percent of women. For the most part, women did not want to participate in such unknown practices, so the sly recruiting agents reverted to various forms of chicanery, including kidnapping.

The brutality and abuse to the indentured Indians by the overseers and drivers are revealed in this narrative. The survivors told their stories to their descendants, who relayed them to the generations that followed. The horrors started with the nefarious practices of the recruiters and the kidnappers. People were held at crowded depots in places like Calcutta. and eventually loaded on ships—sometimes by force. Some people jumped overboard and perished. Many died during the long perilous journey across the oceans. Many women were sexually abused by the ships’ personnel. The survivors who reached their final destinations were treated like chattel and assigned to the various British plantations to work as field laborers. Their housing was inadequate for human habitation. People died there from diseases unknown to them. The work was demanding, and the food was insufficient. Physical and verbal abuses were standard practices. Men and women were beaten. But, the worst was the sexual abuse of the women. The male “authorities” assumed that they could have any woman they wanted at any time. Women who Rejected them had consequences.

Field supervisors made it difficult for many who could not finish their scheduled daily tasks. The penalty for that was extending their bound period to the plantations indefinitely. Women who did not cooperate with the supervisors’ demands had their tasks harshly judged, again, resulting in being bound to the plantation for an extended time. Because of this, some died before completing their indenture.

There were murders, suicides, infanticides, and other inhumane practices. Many babies died from diseases, malnutrition, and inadequate parental supervision due to parents being in the fields. Child abuse was standard practice resulting in low self-esteem for generations to follow.

This book reveals the personal experiences of my ancestors who emigrated from India to Guyana on various ships during the indentured process. Some came willingly, and some did not. This is a narrative of their collective memories and stories about their lives on the plantations and beyond. Some experiences were good, and some were horrible. Even the good stories reflect the turmoil and determination it took to survive in a place where human dignity was compromised to its lowest level. Although the stories are reflections of members of one family, many others dealt with similar issues. This writing is universal for those descendants of the global Indian indentured process who do not know details about their respective ancestors. It is our story. It is our heritage. No matter to which part of the globe those ancestral people went, the gist of their stories is universal. They all suffered a similar fate and should be honored and praised for tolerating and surviving the re-invented and redefined slavery system, a servitude system that contracted innocent people. This contract system became a life sentence for some. These little-known atrocities need to be told and the human race should consider what we are capable of when given unlimited power over others. This book is written to show the world what can happen when systems fail, and money and greed supersede human dignity. Where the wisdom of divine higher powers was assigned lower seating, and chose to dwell among and to comfort the abject sufferers during their darkest moments.

Today it is all history. The abusers and the abused have long departed emptyhandedly into environments unknown to mortals. But the stories survived. I am honored to share the stories with the world and share that we, their descendants, have evolved to reclaim our family dignity, pay homage to ancestral sufferers, and enjoy the foundations they created for us. We stand on their shoulders and pray for their departed souls. Most of all, we live to show what is possible when opportunities present themselves, and we take advantage of those opportunities. Thank you for exploring our ancestral stories in this book titled Marble, Grass, and Glass.

Prologue

After Columbus rediscovered the western hemisphere, European countries engaged in a series of treaties and battles to claim and occupy territories in that part of the globe. One factor that escalated such tension was the demand for and the production of sugar. As the sugar industry grew, so did the need for field laborers. That created the slave trade that lasted for many decades, where African slaves were kidnapped and sold into slavery in the western hemisphere. However, emancipation was enacted over time, which left the wealthy planters starved for an adequate labor force. One such colony was British Guiana, now Guyana, where slavery was abolished in 1834. After an Apprenticeship period, the colony was starved for adequate labor.

The colony of British Guiana changed hands a few times. Sugar production started there in 1658 by the Dutch and was supervised by Nova Zeeland Company. The British took control of the territory in 1781. Dutch regained power in 1784. Finally, the British regained their rule in 1796, which lasted until 1966, when the colony gained independence. Guyana continues to produce good quality sugar that is still being sold under the brand name of Demerara Sugar.

Sir John Gladstone, of Fasque 1st Baronet, a member of British Parliament, father of future Prime Minister William Gladstone, was one of those British plantation owners in Guyana. He desperately went in search of a new and suitable labor force to work his sugar cane fields.

On January 4th, 1836, John Gladstone wrote a letter to Gillanders, Arbuthnot & Co. of Calcutta, India, investigating acquiring a suitable workforce from India. On June 6th, 1836, Gillanders, Arbuthnot & Co., to John Gladstone approved the inquiry. That initiated the 1838 process of Indian indentured servants going to Guyana on a contract basis to work on the various sugar plantations.

That enactment evolved into a glorified slavery system that resulted in a corrupt and venal process that lasted until 1917. It was a system of servitude that re-invented and redefined slavery. John Gladstone and his lobbying cronies created a system:

- Where affluence superseded human dignity, money and power talked, and people suffered.

- Where physical and sexual abuses were acceptable practices. People were beaten and raped.

- Where wealth and power through venality became standard, the Plantocracy, a West Indian lobbying group, controlled the system, including politicians.

- Where the perception existed that not all people were created equally.

- Where fraud and nefarious practices became the norm.

- Where cats were in charge of guarding the bowls of milk.

- Where atrocities existed in the face of blinded eyes, they saw but refused to notice.

- Where Truth Sayers were ethically, morally, and financially ruined —they were outcasted.

- Where many bad things happened to good people, and evil was tolerated.

- Where bad foods and poor nutrition, coupled with stress and exhausting physical labor killed many.

- Where in one colony in one year, over 60 percent of babies died, and their mothers were blamed for their poor maternal instincts.

- Where abuse and shame were too painful to tell, and many tragic secrets got buried with victims’ bones.

The stories of those indentured servants must be told before they are forgotten forever. The victims should be understood, the brave should be praised and the aggressors must be condemned. The following pages reveal some real stories of a family representative of all families who descended from such an atrocious system. This is their story.

Reviews

The US Review of Books | Reviewed by: Kate Robinson

Written in a biographical fiction style, this poignant yet triumphant hybrid memoir/biography documents the author’s heritage as a descendant of East Indian indentured servants bound to work on British sugar plantations. This system lasted from 1838 until 1917. Some of Moteelall’s family members were among the estimated 240,000 souls who emigrated to British Guiana (now Guyana), a “story of servitude contract that resulted in life sentences for many . . . an atrocious system that reinvented and redefined slavery.”

While some people signed indentured contracts of their own free will, seeking a better life, others were kidnapped or tricked into boarding ships bound for the tropics. Whether married or single, women were often subject to sexual abuse by sailors and overseers on the months-long sea voyages and in the cane fields. Those who refused to succumb to these demands suffered constant verbal abuse and hard field labor for less pay. Some laborers died in misery from disease and exhaustion, often leaving orphaned children behind. In contrast, others had the good fortune to buy their freedom early and rebuilt their lives as farmers and merchants in the Hindu communities of colonial Guiana.

Moteelall’s effort to document his family history was a forty-year journey undertaken with much patience and empathy. His appreciation of sensory detail and dramatic story flow makes his ancestors’ joys and sorrows vivid and brings his contemporary family life into sharp focus. The beauty of the human heart and an appreciation for small daily miracles shine through the carefully crafted prose, hindered only slightly by a lack of dialogue and an emphasis on direct narrative. This memoir will enlighten and entertain readers who appreciate a deeply human story set amidst a sweeping historical background.

RECOMMENDED by the US Review

Pacific Book Review | Reviewed by: David Allen

The Nobel prize in literature for 2021 was awarded to the novelist Abdulrazak Gurnah, for his compassionate depiction of the effects of colonialism and the fate of the refugee in the gulf between cultures and continents. This Nobel award speaks directly to the ongoing centrality and relevance of uncovering and publicizing the consequences of the horrors of colonialism.

Marble, Grass, and Glass, a novel by B. Sham Moteelall, is a necessary link in our evolution toward awareness, refutation and reparation of the centuries’-long damage inflicted by slavery on every continent in the world.

Sham Moteelall’s novel describes in minute and captivating detail the plundered lives of a handful of (subcontinental) Indians who agreed to or who were otherwise flummoxed into indentured servitude. (The distinction from slavery is mostly academic and a matter of word choice; the fact is that many of the 1.2 million Indians who were transported to British Guiana led lives of enforced misery, featuring disease, sickness, and premature death.) Sugar plantations were ‘starving’ for cheap labor and the colonial scheme dovetailed nicely into this need. Moteelal makes the point that for some, the transplantation to plantations in the New World actually meant improved lives and increased well-being. One of the many virtues of this book is its historical accuracy and its heartbreaking narrative of the twin scourges of India’s caste system and of the British colonial rule in India.

Books like Marble, Grass, and Glass are important because they provide windows into the suffering humanity and characters behind the historical events. They are perhaps even more important because depredations such as these continue to this day in many parts of the world.

Moteelall’s book opens the world of a cast of memorable characters who suffer to overcome sometimes pitiless odds in the service of making things better for themselves and their families. The book takes us on a whirlwind tour of births, deaths, marriages, incarnations and avatars that gild history with relatable human drama. The protagonists in the book’s many episodes suffer falls from Brahmin class to beggars, are victims of guile and greed, and emerge as the progenitors of Guyanese descendants, many of whom have heroically emerged as success stories in that South American country and elsewhere.

Read Marble, Grass and Glass for adventure, for history, for the many good stories it contains. Sham Moteelall also succeeds as a convincing and engaging writer: these true-to-life tales are couched in the language of fable contemporary fable–and the prose is smooth, articulate and riveting.

New Book Release!

A Common Vision emphasizes various aspects of life with special emphasis on business leadership, management, and other entities.